How Your Gut Microbiome Influences Mood, Immunity, and Weight

Have you ever noticed that when you feel anxious or emotionally overwhelmed, your stomach seems to “act up” as well—causing pain, diarrhea, or discomfort? Or that when your digestion feels off for several days, your mood becomes irritable, low, or restless for no obvious reason? These experiences are not coincidental. Growing scientific evidence suggests that the gut is far more than a digestive organ—it is an active communication hub deeply involved in emotional regulation, immune defense, and metabolic balance. At the center of this system lies the gut microbiome.

The gut microbiome refers to the vast and diverse community of microorganisms—primarily bacteria—that inhabit the human gastrointestinal tract. Their total number exceeds that of human cells in the body. In recent years, the microbiome has emerged as a critical research frontier in mental health, immune dysfunction, and metabolic disorders such as obesity. The brain and the gut are in constant communication through neural, hormonal, and immune pathways collectively known as the gut–brain axis. The microbiome plays a central role in modulating this dialogue.

Microbial Diversity: The Foundation of Health

Studies consistently show that a diverse gut microbiome is associated with better overall health. Among individuals without underlying disease, the average number of beneficial bacterial species is significantly higher than in those with chronic illness. Similarly, people with healthy body weight tend to harbor a richer population of beneficial microbes compared to individuals with obesity.

Research from KU Leuven in Belgium found that people with depression exhibited reduced microbial richness and diversity, and that these differences were associated with both the occurrence and severity of depressive symptoms. These findings suggest that gut bacteria are not passive bystanders but active participants in mental and physical health.

The health effects of the microbiome are largely mediated by the chemical compounds it produces. These microbial metabolites influence cholesterol transport, inflammation regulation, fat metabolism, and insulin sensitivity—processes that are fundamental to mood stability, immune resilience, and weight control.

Mood and the Gut: Conversations with the “Second Brain”

The gut is often referred to as the body’s “second brain,” and for good reason. Approximately 90% of the body’s serotonin—a neurotransmitter closely linked to feelings of calm, happiness, and emotional stability—is produced in the gut. Certain beneficial bacteria help convert dietary tryptophan into serotonin and its precursors, indirectly shaping emotional well-being.

Chronic psychological stress can disrupt this delicate microbial ecosystem. Research suggests that microbiome imbalance not only increases the risk of anxiety and depression but may also interfere with vitamin B6 metabolism. Vitamin B6 is essential for the synthesis of several neurotransmitters, meaning its disruption can directly affect mood and behavior.

The relationship between emotions and gut health is bidirectional. When you feel nervous—such as before public speaking—the brain signals the gut, often resulting in abdominal discomfort. Conversely, when gut health deteriorates due to microbial imbalance or intestinal barrier dysfunction, inflammatory signals can travel back to the brain, contributing to low mood or emotional instability.

Beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are considered key mediators of this balanced communication. Individuals with greater stress resilience often show microbial activity associated with reduced inflammation and stronger gut barrier integrity.

Beyond general patterns, specific bacterial strains have demonstrated targeted effects. For example, Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 has been shown to alleviate depressive symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Neuroimaging studies suggest this strain may influence neural activity in brain regions responsible for emotional regulation. Chronic stress, on the other hand, tends to reduce bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), while certain probiotic combinations may lower cortisol levels, helping establish a positive feedback loop between emotional and gut health.

Immunity: The Gut as a Training Ground

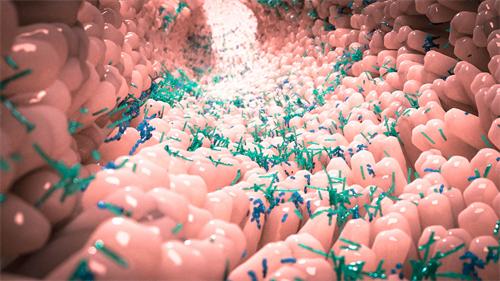

The gut is the largest immune organ in the human body, and the microbiome functions as its primary instructor. A healthy microbial community provides “colonization resistance” by occupying physical space and consuming nutrients, making it difficult for harmful pathogens to establish themselves.

The human body also produces proteins that act like molecular recognition systems, identifying specific beneficial microbes. Once recognized, these microbes release signals that help the immune system stay alert without overreacting. This balance is crucial, as excessive immune responses can lead to chronic inflammation or autoimmune disorders.

When beneficial bacteria ferment dietary fiber, they produce short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate. These compounds play a vital role in immune regulation, enhancing the function of immune cells and promoting the development of regulatory T cells. These cells act as the immune system’s “peacekeepers,” preventing excessive inflammatory responses and reducing the risk of allergies and autoimmune diseases.

Body Weight: The Internal Energy Manager

The gut microbiome strongly influences how the body extracts and stores energy from food. Not everyone derives the same number of calories from identical meals. Studies suggest that individuals with obesity often harbor higher proportions of bacteria capable of efficiently extracting energy from complex carbohydrates.

Certain microbial metabolites, such as 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, can signal intestinal cells to reduce fat absorption and regulate genes involved in fat storage. The microbiome also influences the release of appetite-related hormones, including glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY, thereby affecting hunger, satiety, and food intake.

Unhealthy diets can disrupt microbial balance, promoting the growth of harmful bacteria and triggering chronic low-grade inflammation. This persistent inflammatory state interferes with metabolic regulation and increases the risk of obesity and fatty liver disease. In contrast, a healthy microbiome helps suppress inflammation and creates an internal environment less conducive to fat accumulation.

Building a Long-Term Partnership with Your Microbiome

Defining a universally “healthy” gut microbiome is challenging. Its composition is shaped by diet, environment, age, circadian rhythms, and lifestyle factors. Among all interventions, dietary adjustment remains the most effective and accessible.

Dietary fiber—from whole grains, legumes, vegetables, and fruits—serves as the primary fuel for beneficial bacteria. Research indicates that diets rich in vegetables and fermented foods can reduce perceived stress levels. Under professional guidance, targeted probiotic supplementation may offer additional benefits. For instance, Akkermansia muciniphila has shown promise in metabolic regulation and anxiety reduction. Prebiotics such as inulin act as specialized nourishment for beneficial microbes.

Antibiotics, while sometimes necessary, indiscriminately disrupt microbial communities. When their use is unavoidable, post-treatment microbiome recovery should be guided by healthcare professionals.

Each person’s microbiome is as unique as a fingerprint, shaped by genetics, birth method, early feeding, antibiotic exposure, and long-term habits. Regular sleep and meal timing are equally important, as the microbiome follows circadian rhythms. Irregular schedules, late nights, and nighttime eating can disrupt microbial cycles, increasing inflammation and metabolic dysfunction.

Dietary diversity is essential. Vegetables of different colors contain distinct phytochemicals and fibers that nourish different microbial species. Natural fermented foods—such as yogurt, kefir, kimchi, kombucha, miso, and fermented soybeans—provide beneficial bacteria, while foods like onions, garlic, leeks, asparagus, bananas, and Jerusalem artichokes supply inulin and fructooligosaccharides.

Understanding the gut microbiome ultimately means recognizing that you are not “managing” microbes—you are cultivating a dynamic internal ecosystem. Every daily choice in food and lifestyle is a vote for that ecosystem. Over time, consistent positive choices help build a resilient microbiome that supports emotional stability, immune strength, and metabolic health.

This article is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute medical or nutritional advice. Individual health needs and responses may vary. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional before making any significant changes to your diet, supplements, or medical care.

References

[1] Kelly JR, Borre Y, O' Brien C, et al. Transferring the blues: Depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;82:109-118.

[2] Browning KN, Travagli RA. Central nervous system control of gastrointestinal motility and secretion and modulation of gastrointestinal functions. Compr Physiol. 2014;4(4):1339-1368.

[3] Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2012). Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(10), 701–712.

[4] Turnbaugh, P. J., Ley, R. E., Mahowald, M. A., et al. (2006). An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature, 444, 1027–1031.

[5] David, L. A., Maurice, C. F., Carmody, R. N., et al. (2014). Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature, 505(7484), 559–563.

Recommended for you