Smart Packaging That Tracks Food Freshness

For most of modern history, food packaging has played a largely passive role. Its primary functions were to contain food, protect it from contamination, extend shelf life through physical barriers, and provide basic information such as ingredients and expiration dates. Yet as global food systems become more complex, supply chains stretch across continents, and consumers demand greater transparency, safety, and sustainability, traditional packaging is no longer enough. This is where smart packaging that tracks food freshness enters the picture, representing a profound shift from passive containment to active communication between food, environment, and consumer.

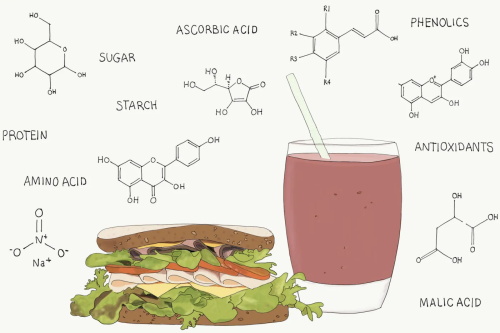

Smart freshness-tracking packaging is not a single technology but a convergence of food chemistry, materials science, sensor engineering, microbiology, and data analytics. At its core, it seeks to answer a deceptively simple question: Is this food still safe and high quality to eat right now? The answer, however, depends on dynamic biological and chemical processes that unfold over time, influenced by temperature, oxygen, humidity, microbial growth, and handling conditions. Static expiration dates printed on packages can only approximate this reality, whereas smart packaging aims to monitor it directly.

Why Traditional Expiration Dates Are Fundamentally Flawed

To understand the value of smart freshness indicators, it is necessary to examine the limitations of conventional “best before” and “use by” dates. These dates are typically determined under standardized laboratory conditions that assume ideal storage temperatures and minimal handling variability. In real life, food experiences temperature abuse during transport, fluctuating refrigeration conditions, and consumer behaviors such as repeated opening and closing of packaging. As a result, two identical products with the same printed expiration date may differ significantly in freshness and safety.

From a food science perspective, spoilage is not a binary event that suddenly occurs on a specific date. It is a continuum driven by enzymatic reactions, lipid oxidation, protein degradation, and microbial metabolism. For example, psychrotrophic bacteria can grow slowly even under refrigeration, producing metabolites that alter odor, texture, and safety well before a printed date arrives. Conversely, food that has been consistently stored at optimal temperatures may remain safe beyond its labeled date, leading to unnecessary waste when consumers discard it prematurely.

Smart packaging attempts to close this gap by responding to real-time conditions rather than assumptions, transforming packaging into an information-rich interface.

Core Technologies Behind Freshness-Tracking Smart Packaging

Smart packaging technologies designed to track food freshness can be broadly divided into indicators, sensors, and data-enabled systems, though in practice many solutions combine elements of all three.

Time–temperature indicators (TTIs) are among the most established technologies. These indicators undergo predictable physical or chemical changes based on cumulative temperature exposure over time. For instance, a dye diffusion system may gradually change color faster at higher temperatures, visually signaling whether a product has experienced excessive heat exposure. TTIs do not directly measure spoilage compounds, but they correlate strongly with microbial growth kinetics, making them particularly useful for chilled and frozen foods such as meat, seafood, and dairy.

More advanced freshness indicators respond to specific biochemical markers of spoilage. Many protein-rich foods release volatile nitrogen compounds, such as ammonia, trimethylamine, and biogenic amines, as bacteria break down amino acids. Smart labels incorporating pH-sensitive dyes or gas-reactive pigments can detect these compounds and visibly change color when spoilage reaches critical thresholds. This approach aligns closely with food microbiology, as it tracks the metabolic byproducts of microbial activity rather than relying on time alone.

Gas sensors embedded in packaging represent another important category. Modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) often uses controlled levels of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen to slow spoilage. Smart sensors can monitor changes in gas composition, detecting oxygen ingress due to package leaks or microbial respiration that increases carbon dioxide levels. These changes can be translated into visual signals or digital data, alerting suppliers and consumers to compromised packaging integrity or advancing spoilage.

Digital and Connected Packaging: From Labels to Data Ecosystems

While visual indicators are powerful due to their simplicity, the integration of digital technologies has expanded the scope of smart freshness-tracking packaging dramatically. Radio-frequency identification (RFID), near-field communication (NFC), and QR-code-enabled smart labels allow freshness data to be stored, transmitted, and analyzed across the supply chain.

For example, a package equipped with an RFID-based temperature sensor can continuously log thermal exposure from production to retail. This data can be accessed wirelessly by logistics managers, enabling dynamic shelf-life prediction rather than fixed expiration dates. In food science terms, this approach aligns with predictive microbiology models, which estimate microbial growth rates based on environmental conditions. When real-world data feed into these models, shelf-life assessments become more accurate and individualized for each package.

At the point of purchase or use, digitally enabled packaging that incorporates NFC technology can connect directly with a consumer’s smartphone to deliver real-time information about the product’s condition. Instead of relying on a fixed expiration label, users can access data reflecting how the food has been stored, whether it has experienced temperature fluctuations, and how close it may be to quality or safety limits. Some systems can even translate this information into practical advice, such as recommending prompt consumption or suggesting additional cooking precautions. In this way, food safety messaging evolves from a static date printed on the package into a dynamic, situation-aware communication tailored to the actual history of the product.

Materials Science: Designing Packaging That Can Sense and Respond

The effectiveness of smart freshness-tracking packaging depends heavily on advances in materials science. Sensors and indicators must be food-safe, stable over the product’s shelf life, inexpensive, and compatible with large-scale manufacturing. This has driven innovation in biopolymer-based films, nanocomposites, and functional inks.

Nanotechnology plays a particularly significant role. Nanoscale materials such as metal oxide nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, and graphene-based sensors can detect minute changes in gas composition or humidity with high sensitivity. When incorporated into packaging films or printed as conductive inks, these materials enable low-cost, disposable sensors that would have been impractical a decade ago.

Equally important is the move toward biodegradable and sustainable smart packaging materials. Traditional electronic components raise concerns about environmental impact, especially given the high volume of single-use packaging. Researchers are now developing paper-based sensors, edible indicators, and compostable substrates that align freshness tracking with sustainability goals. This intersection of food science and environmental science is critical, as reducing food waste through smart packaging must not come at the cost of increased plastic or electronic waste.

Implications for Food Safety and Public Health

From a public health perspective, smart packaging that tracks freshness has the potential to significantly reduce foodborne illness. Many outbreaks are linked not to grossly spoiled food but to products that appear acceptable yet harbor pathogenic microorganisms due to improper storage. By providing real-time freshness and temperature abuse indicators, smart packaging can alert consumers and retailers to elevated risk before consumption.

For vulnerable populations such as pregnant individuals, young children, older adults, and immunocompromised people, this added layer of information is particularly valuable. It supports more nuanced decision-making, such as avoiding foods that have experienced borderline storage conditions even if they are technically within their expiration date.

At the systemic level, smart packaging enables better traceability and faster response during recalls. If freshness-tracking data indicate a pattern of temperature abuse within a specific distribution route, interventions can be targeted more precisely, reducing economic losses and protecting consumer trust.

Food Waste Reduction and Sustainability Benefits

One of the most compelling arguments for smart freshness-tracking packaging is its role in addressing global food waste. A significant portion of household and retail food waste results from confusion or mistrust around expiration dates. Consumers often discard food “just in case,” even when it remains safe and nutritious.

By replacing ambiguous dates with dynamic freshness indicators, smart packaging can extend the perceived and actual usable life of food. Studies in behavioral science suggest that visual freshness cues are more persuasive than printed dates, encouraging consumers to rely on sensory-relevant information rather than conservative assumptions.

In retail environments, dynamic pricing strategies can be paired with freshness-tracking data, allowing stores to discount products approaching the end of their real shelf life rather than an arbitrary date. This not only reduces waste but also improves food accessibility by offering lower-cost options without compromising safety.

Challenges, Limitations, and Ethical Considerations

Despite its promise, smart packaging that tracks food freshness faces several challenges. Cost remains a major barrier, particularly for low-margin food products. While sensor prices continue to fall, large-scale adoption requires solutions that add minimal cost per unit.

Accuracy and interpretation are also critical concerns. Freshness indicators must be carefully calibrated to avoid false positives that trigger unnecessary waste or false negatives that compromise safety. Clear communication is essential, as consumers may misinterpret color changes or digital readouts without proper education.

Data privacy and ownership emerge as new ethical questions in connected packaging systems. When freshness data are collected and transmitted, especially at the consumer level, questions arise about who owns this information and how it can be used. Transparent governance frameworks will be necessary as packaging becomes part of the broader Internet of Things.

The Future of Freshness: Toward Intelligent Food Systems

Looking ahead, smart packaging that tracks food freshness is likely to evolve from standalone indicators into integrated components of intelligent food systems. Advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning will allow freshness data to be combined with predictive models, consumer behavior insights, and sustainability metrics. Packaging may not only tell us whether food is fresh but also suggest optimal storage practices, recipes to use food before spoilage, or redistribution pathways for surplus products.

In this sense, smart packaging represents more than a technological upgrade; it reflects a philosophical shift in how society understands freshness, safety, and responsibility. By making the invisible processes of food spoilage visible and understandable, it empowers consumers, improves public health, and moves food systems closer to a model that values both scientific precision and environmental stewardship. It transforms packaging from a silent container into an active participant in the journey from farm to fork, redefining freshness not as a date on a label, but as a measurable, dynamic state informed by real-world conditions.

Sources

1. Doyle, M. P., & Buchanan, R. L. (2013). Food Microbiology: Fundamentals and Frontiers (5th Edition). ASM Press.

2. Fellows, P. (2009). Food Processing Technology: Principles and Practice (3rd Edition). Woodhead Publishing.

3. Kerry, J. P., O’Grady, M. N., & Hogan, S. A. (2006). Past, Current and Potential Utilisation of Active and Intelligent Packaging Systems for Meat and Muscle-Based Products: A Review. Meat Science.

4. Realini, C. E., & Marcos, B. (2014). Active and Intelligent Packaging Systems for a Modern Society. Meat Science.

5. Duncan, T. V. (2011). Applications of Nanotechnology in Food Packaging and Food Safety: Barrier Materials, Antimicrobials and Sensors. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science.

6. Kiritsis, D. (2011). Closed-loop PLM for Intelligent Products in the Era of the Internet of Things. Computer-Aided Design.

Recommended for you